Friday, March 11, 2011

March of the Beetles

So you can imagine my excitement and disappointment when on my way to work this morning I saw that wonderful eater of aphids, a ladybug, squished on the sidewalk. This is practically the first outdoor insect I have seen this spring, and just the one I wanted to catch and put on my plants, but it had been stepped upon.

Knowing that the ladybugs were waking from hibernation, I kept an eye out for them on the rest of my walk, and at lunch time. I collected a dozen, and am prepared to offer advice on the finding of ladybugs on cold spring days. Look for them climbing out of dense vegetation (evergreen shrubs, tall dead grass) upon which the sun is shining in places sheltered from the cold wind. If you see one, look closely for more nearby, as they tend to overwinter in groups. Ladybugs are poisonous to most things that might want to eat them, and will come out of cover into the sun even when they are too cold and slow to fly or escape, and are therefore easy to catch. Generally a slightly moist finger touched to the wing covers will adhere enough to lift the beetle into a jar without risk of squishing them. Once you have handled them they will arouse quickly, and attempt to climb to the top of whatever container you have but them in. Apply them liberally to plants infested with aphids, whiteflies or other pests, and expect to find them crawling around your apartment.

Tuesday, March 08, 2011

Acronymic Challenge

Some colleagues and I are now discussing starting an actual scientific society for evolutionary demography, and it needs a good acronym. I suggested Society for Ecological and Evolutionary Demography (SEED) but was shot down on the grounds that I had added Ecology to the society just for the acronym. So I'm still thinking here, and wonder if you have any good ideas.

It has to have the words "Evolutionary Demography" in it and some word that means society or association. It can have the word "International" if the I helps. Keep in mind that this is going to be an actual scientific society, so nothing ridiculous, scatological or overtly jocular will do.

Now, I should clarify I'm not actually in charge here, so I don't necessarily get to pick the name, but if you propose something sufficiently clever, appropriate and memorable, I'll propose it, and you may have the honor of naming a scientific society.

Thursday, March 03, 2011

Excited to teach again

Summer Semester 2011

IMPRSD 189

Introduction to Evolutionary Demography

| Start: | 4 July 2011 |

| End: | 9 July 2011 |

| Location: | Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (MPIDR), Rostock, Germany |

Instructors:

- Daniel Levitis, MPIDR

- Hal Caswell, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

- David Thomson, University of Hong Kong

- Annette Baudisch, MPIDR

- Alexander Scheuerlein, MPIDR

- Oskar Burger, MPIDR

- Maren Rebke, MPIDR

Course description:

Understanding survival, reproduction and other life-history events is central to the study of both demography and evolutionary biology, and each field has developed methods and concepts to observe patterns and elucidate principles. The growing field of evolutionary demography treats demographic variables (patterns of survival, reproduction, and development) as properties of organisms that reflect evolutionary processes, just as morphology, behavior, and physiology do. It draws on both disciplines to search for evolutionary explanations of demographic patterns in terms of adaptation, genetics, phylogeny, and the environment. Further, it applies demographic methods and reasoning to answering evolutionary questions. Demography and evolutionary biology are conceptually unified and inextricably linked, so the questions we want to answer can best be tackled by traversing traditional disciplinary boundaries. This course is intended to introduce early career researchers from both fields to the concepts, methods, challenges and questions of evolutionary demography.

Course structure:

We will begin with an introduction to classical evolutionary demography and the motivations for combing evolution and demography, incorporating enough basic evolutionary theory and demographic theory to get everyone on the same page. We will then focus on current topics in evolutionary demography, including:

- Aging across the Tree of Life: Measures and Patterns

- Sex-specific differences in mortality patterns: Evolution in action

- Modes of adaptive explanation of demographic patterns: a survey

- The pace and shape of aging

- The evolution of mortality of the young

- Age specific reproduction in the wild

- Life-history allometry and Charnovian invariants

Finally, pairs of students will be asked to spend the afternoons of the 7th and 8th preparing short presentations, to be presented on July 9th. Each pair will discuss the evolutionary basis of a different demographic trait or phenomenon, what is known about it and how it can be investigated.

Organization:

For July 4-8, each morning will consist of two lectures (one hour each) and each afternoon will have a one hour lab. Then the afternoon of July 9th will be occupied with short presentations by pairs of students.

Prerequisites:

Students should be familiar either with the basics of demographic life-table methods, or with evolutionary theory. Familiarity with Stata or R software will be very helpful.

Examination:

Students will be evaluated on participation in class and on short presentations.

Financial support:

There is no tuition fee for this course. Students are expected to pay their own transportation and living costs. However, a limited number of scholarships are available on a competitive basis for outstanding candidates.

Recruitment of students:

- Applicants should either be enrolled in a PhD program or have received their PhD.

- A maximum of 16 students will be admitted.

- The selection will be made by the MPIDR based on the applicants’ scientific qualifications.

How to apply:

Applications should be sent by email to the MPIDR. Please begin your email message with a statement saying that you apply for course IMPRSD 189 - Introduction to Evolutionary Demography.

- You also need to include the following three documents, either in the text of the email or as attached documents. (1) A two-page curriculum vitae, including a list of your scholarly publications. (2) A one-page letter from your supervisor at your home institution supporting your application. (3) A one-page statement of your research and how it relates to course IMPRSD 189. Please indicate whether you would like to be considered for financial support.

- Send your email to Heiner Maier (office@imprs-demogr.mpg.de).

- Application deadline is 31 March 2011.

- Applicants will be informed whether they will be admitted by 15 April 2011.

Readings:

The course will make use of readings from:

- Baudisch, A. 2011. The pace and shape of ageing. Methods in Ecology and Evolution. DOI: 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2010.00087.x

- Caswell, H. 2001. Chapter 11, Matrix population models. Sinauer.

- Jones, O. R., Gaillard, J. M., Tuljapurkar, S., Alho, J. S., Armitage, K. B., Becker, P. H., Bize, P., Brommer, J., Charmantier, A. & Charpentier, M. 2008 Senescence rates are determined by ranking on the fast-slow life history continuum. Ecology Letters 11, 664-673.

- Levitis, D. A. 2011 Before senescence: the evolutionary demography of ontogenesis. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 278, 801-809.

- Metcalf, C. J. E. & Pavard, S. 2007 Why evolutionary biologists should be demographers. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 22, 205-212.

- Rebke, M., Coulson, T., Becker, P. H. & Vaupel, J. W. 2010 Reproductive improvement and senescence in a long-lived bird. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107, 7841-7846.

- Vaupel, J. W., Baudisch, A., Dolling, M., Roach, D. A. & Gampe, J. 2004 The case for negative senescence. Theoretical Population Biology 65, 339-351.

Additional reading material will be provided at the beginning of the course.

A reviewer's lot is not an'appy one

Suppose you are a scientist, and suppose you get an email asking you to peer-review a paper. This email contains the abstract of the paper, so that you can assess whether you are qualified to review the paper. Reading the abstract, you find that you are qualified, as the topic is one you know well. You also notice that you are deeply skeptical of the argument being made, and that you are very likely to recommend that the article not be published. What is your professional duty? Should you try to read the article with an open mind, despite your misgivings, or should you simply decline to review it out of fear of being biased?

In this situation, I did the former, reasoning that if we only review article we are sympathetic to, many terrible articles will be published simply because skeptical reviewers eliminated themselves, and some good articles with unpopular claims will be rejected for lack of qualified reviewers. I read the article, found it irreparably flawed in several major respects, and suggested that the journal reject it. I looked hard for nice things to say about it and didn't find much. While I'm confident my review was accurate, I'm glad these things are anonymous.

Finally out

A measure for describing and comparing postreproductive life span as a population trait

Summary:

While classical life-history theory does not predict postreproductive life span (PRLS), it has been detected in a great number of taxa, leading to the view that it is a broadly conserved trait and attempts to reconcile theory with these observations. We suggest an alternative: the apparently wide distribution of significant PRLS is an artefact of insufficient methods.2. PRLS is traditionally measured in units of time between each individual’s last parturition and death, after excluding those individuals for whom this interval is short. A mean of this measure is then calculated as a population value. We show this traditional population measure (which we denote PrT) to be inconsistently calculated, inherently biased, strongly correlated with overall longevity, uninformative on the importance of PRLS in a population’s life history, unable to use the most commonly available form of relevant data and without a realistic null hypothesis. Using data altered to ensure that the null hypothesis is true, we find a false-positive rate of 0·47 for PrT.

3. We propose an alternative population measure, using life-table methods. Postreproductive representation (PrR) is the proportion of adult years lived which are postreproductive. We briefly derive PrR and discuss its properties. We employ a demographic simulation, based on the null hypothesis of simultaneous and proportional decline in survivorship and fecundity, to produce a null distribution for PrR based on the age-specific rates of a population.

4. In an example analysis, using data on 84 populations of human and nonhuman primates, we demonstrate the ability of PrR to represent the effects of artificial protection from mortality and of humanness on PRLS. PrR is found to be higher for all human populations under a wide range of conditions than for any nonhuman primate in our sample. A strong effect of artificial protection is found, but humans under the most adverse conditions still achieve PrR of >0·3.

5. PrT should not be used as a population measure and should be used as an individual measure only with great caution. The use of PrR as an intuitive, statistically valid and intercomparable population life-history measure is encouraged.

Wednesday, March 02, 2011

Places where I may post postdoc ads

http://www.evolutionsociety.org/jobs.asp

http://www.sdbonline.org/archive/SDBNews/JobsIndexPostdoc.html

http://www.newscientistjobs.com/jobs/browse/biology.htm

http://www.sicb.org/jobs.php3

http://www.benthos.org/Classified-Ads/Jobs-offered.aspx

http://www.eseb2011.de/sponsoring.htm

http://www.evolution2011.ou.edu/sponsor_exhibition.html

http://www.thesciencejobs.com/category/fellowships

https://careers.chronicle.com/webbase/index.jsp

http://www.smb.org/jobs/index.shtml

http://www.math-jobs.com/?nav=employers&nav_sub=post_a_job

http://botany.org/newsite/employment/index.asp

http://www.postdocjobs.com/jobs/jobs2.php?subcatid=37&catid=2

http://evol.mcmaster.ca/cgi-bin/my_wrap/brian/evoldir/PostDocs/

https://listserv.umd.edu/archives/ecolog-l.html

Advertising

It therefore strikes me as somewhat ironic that most of my time this week seems to be consumed with advertising. I am advertising positions available and a summer course in evolutionary demography we will teach here at the Institute. So I write ads, consider how best to appeal to my target audiences, edit them, figure out where to place them, and so forth. Granted, these are very different kinds of ads than the one calibrated to make young women feel bad about wearing any shoes that don't draw blood, but it is still somewhat outside my core competency.

Sunday, February 27, 2011

Recruiting

First, there is the possibility (depending upon my application) that I, and therefore these positions, will be moving to a different institute in a different part of Germany. I should know by mid-April, but until then I need to be somewhat vague as to the location.

Second, my boss is also recruiting, and effectively has first dibs on any of the candidates except those I independently recruit. So there are a couple of interesting candidates coming through the Institute's training courses, but he plans to offer them positions. In so far as there is a pool of local talent, I can't readily draw on it.

Third, although quite a few people have now seen my review article, I am still not widely known. This means no one is going to be just looking me up to see if I have positions available.

Fourth, I need to recruit some people with fairly specific and distinct skill sets and interests. A statistical demographer, a experimentalist to work with small aquatic invertebrates, and a developmental geneticist to start with. Good candidates for these three positions are likely to be reading three different sets of journals, going to three different types of meetings, and so on. Further, what I will ask them to work on is a bit outside the purview of each field, meaning candidates with specific plans for what research they want to do would have to change those plans considerably to fit within the bounds of the project.

Fifth, Rostock as a location is not a big draw. While not a bad lace to live for a few years, the place doesn't add anything to the appeal of the job for most potential applicants.

Finally, while my Institute is very well known to Demographers internationally, most biologists don't know of it and the biology that goes on here, and may be turned off by applying to a demographic institute.

Post-finally, I've not recruited anyone more senior than an undergrad before, and so I'm learning as I go.

Which all goes to say I am going to have to put some time and work into getting the word out. I frankly doubt I will fill each position in the near future, but I sure will try.

Friday, February 18, 2011

news

I will not get the grant. The interview went well, but the Human Sciences committee included no one with knowledge of my field (either of my fields, really), and my claims that no one else is focusing on this important topic, while true, were not entirely believed. Out of >60 applicants, I am told they interviewed 10 and will fund three.

Second, the good news:

I have been encouraged to apply for a nearly identical grant in the Biology section, deadline this Monday. If I don’t get that, I have been generously offered enough funds to recruit a couple of grad students and a post-doc, while keeping my current position. So one way or another I will have a research group, although not necessarily one as well funded or official as I would have had.

Friday, February 11, 2011

Focus

I hope that the distinguished scientists I am to present to on Wednesday will be somewhat more decorous. If they are not, it may give me an unfair advantage over the other applicants.

Wednesday, February 09, 2011

My morning walk

No you can’t make a soup for your belly from your head,It may be a sign of stress, or just plain silliness.

No you can’t make a soup for your belly from your head,

No you can’t make head soup, for you’d surely wind up dead,

No you can’t make a soup from your head.

No you can’t make a soup for your mommy from your head,

No you can’t make a soup for your mommy from your head,

Tell your mom you want soup, she’ll see that you’re well fed,

No you can’t make a soup from your head.

No you can’t make a soup for your wedding from your head,

No you can’t make a soup for your wedding from your head,

If you served self-head soup, then you probably would not wed,

No you can’t make a soup from your head.

No you can’t make a soup for your belly from your head,

No you can’t make a soup for your belly from your head,

No you can’t make head soup, for you’d surely wind up dead,

No you can’t make a soup from your head.

Tuesday, February 08, 2011

All I have to do in 15 minutes...

I have now completely reworked my talk, put the phrase "path breaking" in there, redone all my figures to make them more non-specialist friendly, and made all the font real big in case anyone of the ≤ seven audience members is sitting way at the back of the room. My next task is to run through it several times before my next practice talk this Thursday.

Friday, February 04, 2011

This is why we give practice talks.

I am giving another practice talk next Thursday, this time to complete non-experts. By then I hope to make it comprehensible to that audience.

Thursday, January 27, 2011

Hydra bud

Wednesday, January 26, 2011

Blame the vehicle

Monday, January 24, 2011

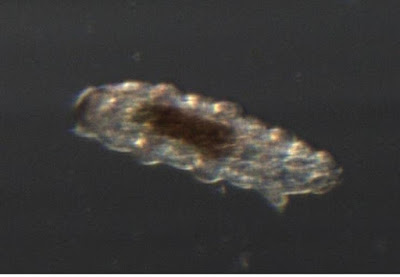

Science picture of the month: Hydra hatchling

I've talked her before about hydra and their reproduction, so I thought I should post a few out of the thousands of pictures I have of them. I particularly like this one, and have a copy o up on the wall in the lab. It is a hydra hatchling, right out of the shell. The three bumps at the lower end of the picture are it's stubby little baby tentacles. The diameter of that shell is a bit under half a millimeter.

Innervation

There is perhaps good reason for concern. The other applicants I’m competing against are likely to be an extraordinary group. I have no indication of what fraction of us they're likely to hire. I have the bare minimum professional experience necessary to apply. I'm a biologist interviewing in the Humanities Section. What to an American seems an appropriate level of self recognition can strike many Germans as immodest boasting. My slides are currently a bit too wordy and dense.

All that said, I don't feel nervous yet; they don't expect me to describe my work in German. Just the idea makes me sweat.

Sunday, January 16, 2011

Linguistic injustice; it's good to be a native Anglophone

All this came to mind when I saw this letter

“Awkward wording. Rephrase”: linguistic injustice in ecological journals

and this response

‘Linguistic injustice’ is not black and white

in the journal Trends in Ecology and Evolution (TREE).

TREE is a high profile journal, publishing mostly excellent review articles, but unfortunately most of its content is not free to the public.

I will quote; the letter’s author, Miguel Clavero, begins,

International scientific communication is monolithically dominated by English, particularly within natural sciences. The professional career of individual scientists relies on their ability to publish in internationally relevant journals, and writing in English is the only way to achieve this. Non-native English speakers (NoNES) seem to be clearly disadvantaged with respect to native English speakers (NES) when trying to get their work published. In fact, English language proficiency has been shown to be a strong predictor of scientific output...

This argument makes sense to me. I have colleagues who are both smarter and harder working than I, who are quite fluent in conversational English, who take much longer to write a paper than I do. Writing crisp, clear, precise, flowing science while staying within word limits is hard, and frankly I’ll never learn a second language well enough to pull it off in anything but English. If Greek, Latin, French, Chinese, Arabic or German were the dominant language of science, I would be in deep trouble.

The response published in TREE points out that other disadvantages (e.g., being from a developing country) are vastly harder to overcome than being NoNES. A Swede has a much better chance to succeed in international science than an Anglophone African. A Swede may even come to speak and write English which is better than that of some Anglophones. It also points out that most English language journals won’t reject a paper because of language problems, so long as the science is sound and the writing is comprehensible and reparable. Both of these things are surely true, but don’t negate Clavero’s point. Bad English may not be a huge disadvantage, but skilled beautiful English is, it seems to me, a big advantage, and native speakers are much more likely to speak a language beautifully. This is particularly true, I think, when it comes to job applications. When one is being evaluated not only on the quality of one’s work, but also on one’s presentation skills, ability to answer complex questions clearly and leadership potential, language skills are important. I have seen application talks at the Institute given in such poor English that I had trouble following them; these people were not hired. The graduate students and post-docs I work with are mostly NoNES; a larger portion of the Research Scientist and lab heads are NES or have lived for extended periods in English speaking countries. This is not because of hiring decisions beeing made inappropriately. Rather, those fluent in English tend to be more successful in those tasks on which hiring decisions are legitimately based.

I doubt that English will cease to be the dominant language of science in my lifetime, and for this I am glad. That said, I take Clavero’s point, and I suppose we should add NoNES to the list of groups disadvantaged in scientific careers (females, underrepresented minorities, the disabled, citizens of developing nations, etc.). I am not sure what is to be done about it. Clavero argues that journals should cover the costs of language editing by charging a fee to all authors, whether they need language editing or not, spreading the costs. They would have to waive this fee for those without sufficient funding to cover them. Some journals in fact already do this, paying in-house language editors from author fees. This has not obviated the linguistic injustice. I am not sure what will, short of sci-fi quality automatic simultanious translation technology. I would love to have this technology, if for no other reason than because then I could stop struggling to learn German.

Friday, January 14, 2011

Weasel words

After reading the Wikipedia article on this, I happened to sit down to edit an application essay by a brilliant, but very shy, student of mine. I found it full of phrases like, "I wanted to," "Although I was," "I believe," "I began to," "I had the opportunity to," and "I helped to." These aren't weasel words mostly, but they serve a similar function. They allow her to say what she accomplished without it seeming like she is saying that she accomplished things. "I designed and carried out the research" reads a lot better than, "I was offered the chance to gain experience in designing research and gathering data," and takes up a lot less space.

The really successful scientists I know not only can say a great deal in very little space, they can squeeze in praise of their own work. I have several times seen, in scientific publications, people describe their own work as startling, revolutionary or subtle. For purely professional reasons, I aspire to this level of unabashidness. For the truly shy, classes in hubris might be in order.

Two talks at once!

Anthropology:

MPI for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig

MPI for Social Anthropology, Halle/Saale

Psychology:

MPI for Human Development, Berlin

MPI for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences, Leipzig

MPI for Psycholinguistics, Nijmegen, Netherlands

Economics:

MPI of Economics, Jena

MPI for Research on Collective Goods, Bonn

Law:

MPI for Foreign and International Social Law, München

MPI for Intellectual Property, München

MPI for Comparative and International Private Law, Hamburg

MPI for Foreign and International Criminal Law, Freiburg

MPI for Comparative Public Law and International Law, Heidelberg

Sociology:

MPI for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity, Göttingen

MPI for the Study of Societies, Köln

MPI for Demographic Research, Rostock

History:

MPI for Art History, Florence, Italy

MPI for the History of Science, Berlin

MPI for European Legal History, Frankfurt/Main

You will note that I put my own institute, Demography, under the heading of sociology. Demography is in many way rooted in sociology, despite my belief that it should be a branch of biology. You will also note the preponderance of topics such as Law, Economics and Psychology, which have little theoretical overlap with evolutionary demography.

This is, in a way, a brilliant way of evaluating an applicant. Anyone who can describe their topic in a way which is simultaneously comprehensible and exciting to experts in one’s own field and experts in distant fields is at least a talented communicator. If they threw in some toddlers, who also had to like my talk, and maybe a few Tea Partiers, then it would be a real challenge.

Wednesday, January 05, 2011

The dead blackbird thing.

Much has been made of the news that 5000 dead blackbirds fell from the sky onto a small Arkansas town at the turning of the year. ~11:30PM on New Year's Eve. Conspiracy theories and omens abound, but I will propose my own theory: a conspiracy between fireworks and the migratory behavior of blackbirds.

There are several species of blackbirds in North America (e.g. Red-winged Blackbirds, Grackles, Starlings), that tend to migrate in large mix-species flocks. And when I say large, I mean blot out the sun, river in the sky, ornithophobe's nightmare large. Frequently in the hundreds of thousands, not rarely in the millions of birds. I was working at the Long Point Bird Observatory (in southern Ontario) one day in late November when one of these blackbird flocks went by, too thickly to count, for an hour and a half. As soon as we saw them we rushed out and closed the mist-nets we had put up to catch birds. While these nets work well for catching a flock of a dozen chickadees (which we would then measure, band and release), a thousand blackbirds hitting the nets all at once will collapse them, potentially killing large numbers of the birds. Many of the nets had several dozen blackbirds in them within the first minute, and it was a struggle to free them faster than new birds got caught. We couldn't close the nets until they were empty, and we couldn't stop catching them without closing the nets, so thick and fast they came, despite the fact that the main stream of birds was far above our heads, and despite each bird tending to avoid places where humans were standing. We put brightly colored cloths in the nets to make them more visible, but still we couldn't keep up. The nets began to sag under the weight of birds, each of which weighed only a few ounces. Only when the course of the avian river shifted significantly to one side were we able to empty and close the nets, and then stand and gape at the immensity of the flock. That night they all settled in a nearby wetland, densely and within a surprisingly small area.

Now by New Years Eve, these flocks would not be in Ontario, but in places more like Arkansas. It is reported that a wooded area in Beebe was being used as a nighttime roost for several hundred thousand blackbirds. My guess is that somebody was setting off fireworks near that wood, and scared the bejesus out of at least half a million blackbirds. Fireworks are used in agriculture to scare blackbirds out of fields, and to uninitiated birds, they are quite terrifying. So this river of blackbirds leaps into the air whirl around and around as the rockets and fountains go up. Now blackbirds, like most songbirds, have very poor night vision, and frequently smack into things if startled up at night. So maybe one in a thousand in the whirling disoriented mass smacked into a lamp, a sign, a building, each other. They go quite fast enough to kill themselves crashing headlong into hard objects, and can rebound several feet. The birds seemed to have died of blunt trauma, as from a crash.

Or it could be a sign of the end times.

Friday, December 31, 2010

A Frigorific New Year!

The temperature of course can't get much above freezing with all this ice all over everything. Looks like a frigorific new year.

Thursday, December 23, 2010

Passed round one

I've been invited to give a short talk on my research to the committee deciding which applicants will be invited to form Research Groups. The interview will be mid-February in Berlin, and I should know very shortly after that if my application was successful.

This means I have a month and a half to write a talk, make impressive figures and graphs, and so forth. The hardest part for me in writing the talk is figuring out who my audience is. The committee that wants to interview me is from the Human Sciences Section. This includes institutes focusing on anthropology, economics, art-history, law, religious and ethnic studies, linguistics, sociology, the history of science and the study of cognition. It also includes demography, evolutionary anthropology and a fair bit of other natural sciences. I can't simply give the same talk to a group of biologists and demographers that I would give to a committee of lawyers and ethnographers. I don't yet know if the committee as a whole will be judging my talk, in which case I have to assume a great diversity of background, or if they will have a smaller group of specialists assigned to each talk. I can give a good talk either way, but not both simultaneously. I've got some thinking to do.

Friday, December 17, 2010

Christmas Party of Science

My favorite part of the party was the Powerpoint Karaoke. This is a game which could be popular only with academics. Each player gets up to give a talk with power-point slides, which sounds boring, until you consider that he has never seen these slides before, and they are on a topic he likely knows nothing about. There were three contestants, including Santa, and each of us prepared a set of slides another one of us had to speak on. We were not kind to each other. My friend Jon spoke first, on a set of slides I had made, on sesquipedalianisms. I had the longest and most complicated words in several languages under the bright red heading “SAY THESE WITH ME!!.” He made a valiant attempt. Next I got up, in costume, and my slides were entirely in Greek. I recognized the alphabet, but had no idea what any of the words said, and there were no pictures. Lucky for me, most of my audience also didn’t read Greek, so I pretended that I knew exactly what the slides said, and that they were designed to correct common misconceptions about Santa (e.g., Santa does not in fact employ any reindeer, as their odor offends his sensitive nose.) The talk went quite well, and only afterwards did I find out that it was a presentation in Greek on numerical modeling. Finally, my friend Mikko got up and gave a talk on obscure economic phenomena he knew nothing about. He did a creditable job of pretending he knew what he was saying, or rather of being so precise in his vagaries that it was a believable if entirely uninformative talk. It was the first time I’d played this game, but I think it will not be the last.

Frohe Weinachten! Ho Ho ho!!!

Saturday, November 27, 2010

Could be good

If he ends up writing about my work it will bring my mother great bragging points with her cousins whether he gets it right or not, but I would be greatly annoyed if he slaughters it.

Competing by not competing

Despite this, I am setting out to write a human demography paper, with little if any evolution in it. I can do this with some confidence because, as far as I know, I am working in an area that has been almost completely overlooked, and therefore I have no competition. Most anyone with a solid demography background could do a better job of what I want to do than I can, and I really couldn't compete. But because they haven't bothered, I don't have to compete. I can do a decent job and hopefully publish in a good journal without worrying about the competition, because I believe there to be none.

In my recent grant application, I wrote, "My work falls between demography and evolution, outside the well explored territory of either. Work within evolutionary demography tends to focus on senescence and reproduction; I have intentionally eschewed these to seek the question others have avoided. This is a high risk strategy; my work does not fit neatly into any one topic-specific journal or discipline. However this unconventional approach has the opportunity to found a new direction of study and investigate the most important questions therein." This is a polite way of saying that I intentionally avoid competition by seeking out the questions others have ignored, or deemed less interesting. Most successful scientists are successful because they look for opportunities to do what others aren't doing. I don't know to what extent other seek out whole areas that others haven't bothered with. I also don't know how successful or sustainable a strategy this is likely to be in the long run. After all, the success of the work will ultimately be measured by how many other people get interested in it, and try to improve upon it. Successful work, by definition, must therefore attract competition. So if I want to be successful, but continue not having competitors, I’ll need to move on to some other under-appreciated topic fairly quickly. As I rather like the topic I’m currently seeding, I may just have to put up with some competition, and try to stay ahead of them. having my own research group would be a great help in this. Not being an expert demographer is less of a problem if you have an expert demographer on staff.

Sunday, November 21, 2010

More Tardigrades

Anyway, here, by popular demand, are a couple more pictures.

Note the long curved claws at the ends of the toes, much like a bear has.

Saturday, November 20, 2010

Fussy Hydra babies

I find myself looking forward to having rotifers in the lab again. They are just so familiar at this point.

Friday, November 19, 2010

The Royal Society has informed me

Focus

Science, like most complex tasks, is much easier to make progress on if you know exactly what you are doing, and you have everything you need to do it ready. Over the last couple of months, I got a lot done because I focused on finishing my grant application, and on getting out the two papers I needed to finish to go with my application. Now the application is in, the review paper is accepted, and the methods paper is submitted, and I must find a new focus to guide me. Over the last couple of days I have been scattering my time and thoughts between a dozen projects, and not really making any progress on any of them. I am giving myself until Monday to decide what the new plan is.

Thursday, November 18, 2010

Tardigrades!

What is so cool about tardigrades? They can survive total dehydration, exposure to vacuum, radiation, freezing, extreme heat, conservative radio personalities, you name it. They can persist for a decade dried out with no signs of life, then just add water and they reanimate themselves. They are rolly and round and shaped kind of like six-legged teddy bears with two more legs growing out of their tails. This appearance has earned them the nickname ‘water bears.’

This afternoon I wanted to see if the hydra I am keeping in the lab would eat rotifers, because the Artemia I am giving them now are a bit too big for them, and rotifers a tiny. I found some in a puddle outside the institute, and in the same puddle, I found tardigrades. I had never knowingly seen a live tardigrade before, so I took a good long look at them under the microscope. These ones were well under a millimeter long, but I tried to get pictures.

They are small enough that really good photos would require a different microscope, but here are two.

This is a tardigrade from above. You can't really see how cute they are from above.

This is the shed skin of a tardigrade.

Just as snakes have to shed their stiff skins occasionally, many animals with exoskeletons molt that shell occasionally. All the arthropods (insects, spiders, crustaceans, crabs etc) will shed their skins, and so will tardigrades. Tardigrades are not arthropods, but are their closest realtive except for the velvet worms. This skin is head-end down. You can clearly see the six legs on the left side, and the two-legged tail at the top-left. I will try to get better pictures of a live critter tomorrow.

Sunday, November 14, 2010

Jon Asks: 2

In the Laura Ingalls Wilder book The Long Winter, Laura's father says that you can predict the severity of a winter by observing the thickness of muskrat nests in the summer. Muskrats, he says, will build thicker nests during the summer if the following winter is going to be relatively colder, and vice versa with thinner nests and relatively warmer winters. Has this folk wisdom been investigated? Is it true? And if so, where can I get my own muskrat colony?

I can't find anything on Google Scholar or Web of Science indicating that anyone has published anything about muskrats and weather prediction, other than this:

Man's natural craving for advance knowledge of coming weather extends thousands of years back of any attempts at scientific weather forecasting. Realizing that he has not the necessary foresight himself, he has imagined animals to be endowed with some peculiar sense which enables them to know, weeks or months ahead, what the weather will be. Thus a large group of animal weather proverbs has come into existence. Millions of people believe that the thickness of fur on a muskrat, or the number of nuts stored by a squirrel, or a supposedly early migration of certain birds, indicates a severe winter. Yet it is certain that animals have no such foresight.

from: Robert DeC. Ward. 1926. The Present Status of Long-Range Weather Forecasting

Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society,Vol. 65, No. 1, pp. 1-14

He provides no evidence to show that they don't, he is just certain. Note that the version you mention has to do with the thickness of the wall of the house, while the version Ward mentions has to do with the thicknesss of their fur. The fur hypothesis would be easier to test, if you were a muskrat hunter. I am frankly doubtful whether he or anyone else has done the work that would be needed to convincingly either story. You would have to measure the wall thickness of bunches of muskrat houses (or the pelt of many muskrats) in the summer. You would have to do this every year for quite a few years in order to make a convincing analysis of the relationship between wall thickness and hardness of winter. You would probably also want to measure various features of the microclimate, the muskrats behavior and physiology, and the local ecology, in order to get some sense of what the mechanism was. You probably would want to measure the pelts and the houses, just to make sure you were measuring the right thing. This is one limitation to testing folk-wisdom. There are often several versions, and it is hard to know if you are testing the right one unless you test all of them, and then you increase your chances of finding a strong correlation just by chance. My best guess is that there is some, but not a lot of, truth to either version of the story. Certainly they could pick up on whatever cues are available that the winter is going to be hard. But like most weather prediction, they probably aren't very accurate, at least not months in advance.

Jon Asks: 1

I've read that fungi are the only organisms that can degrade the longer-chain fibers in wood, such as lignin, and that without saprobic fungi the world would be blanketed in dead, undecayed trees. I see on Wikipedia that it is not literally true that no bacteria can degrade lignins, however, by Wiki's account, it does seem that no known bacteria are very good at it. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ligninase) So why would that be the evolutionary case? Bacteria have evolved to break down pretty much everything else on the planet (roughly speaking), and wood has been around for something like 350+ million years. Why would they be such second-rate degraders when it comes to lignin?

This is an interesting question, but not one I can give a very satisfying answer to. Explanations of why something didn't evolve are always fairly speculative. Why no six legged tigers? Why no live-birthing birds? Why no Ents?

So why no lignin devouring bacteria? If they can do it poorly, why not well? Maybe it isn't worth their while to invest in that capacity, as they are always outcompeted by the fungi who can already do it? Maybe they can rely on the fungi to make the enzymes, and then they can just mooch. Perhaps the process of making the necessary enzymes requires separate cellular compartments, which bacteria lack. Maybe the necessary mutations just never occurred, and so couldn't be selected for. Certainly I don't know.

Friday, November 12, 2010

Winter

I have found that the best strategy for keeping my bad hip from minding the weather is to make sure I am absurdly over-dressed. This morning I walked to work, in temperatures above freezing, wearing high insulated shoes, long-underwear, lined pants, a heavy over-shirt, a down parka and thick gloves, hat and scarf. I was sweating the whole time, but my hip felt fine.

All of this does not endear the city to my heart, and yet I hope I will be here another five years. The grant application that is taking most of my time is to establish a research group of my own, funded by the Max Planck Society for five years. There are three responses they could make to my application. They could say no, they could say yes and let me form the research group here, or they could say yes but tell me to form it at a different Max Planck Institute, in a different city (i.e., Cologne).

I indicate in my application that my first choice is to stay here (at MPIDR), not out of love for the climate, but because of MPIDR’s, “strength in evolutionary demography would be a great benefit to me. I have ongoing collaborations with several MPIDR researchers, including members of the Research Groups on Lifecourse Dynamics and Demographic Change, and Modeling the Evolution of Aging, and of the Laboratories of Statistical Demography, Survival and Longevity, and Evolutionary Biodemography. As my project draws on evolutionary and demographic theory, on MPIDR's Human Mortality Database and Biodemographic Database, on laboratory experiments and survey data, MPIDR’s mixture of social science and biology is the ideal environment for me.”

Add to that that we have good friends, Iris enjoys teaching at the University here, we like our colleagues, we have a great apartment, and moving (which we have done far to much of) is a pain in the rear, and I am very much hoping to stay here. That said, if they offer me a group in Cologne, we will certainly go, in the spring.

Thursday, November 11, 2010

Good news

The point of a review article is to give an overview of the field. What is know, what is hypothesized, what are the important questions, where is the field going. I have been thinking about the topic of this one on and off for perhaps seven years, but if you put together all the time I specifically spent on it, it would be about six months of work, most in the last year. Perhaps half of that was spent just searching out the relevant literature. I must have read several thousand article titles, perhaps 500 abstracts, and maybe 200 full papers and book chapters. 91 sources made it into the final paper, and 18 more into the appendixes. The reason I had to do so much preliminary literature searching is that no one has ever written a review on this topic before, and perhaps four of the authors whose ideas and data I draw on had this general topic in mind.

Now, part of publishing with them and most other journals these days is that the paper is embargoed until they say it ain't. Embargoed means I can't tell the press what I found out, or even what the article is about, before the journal has a chance to publish it. But for the curious and bored, I can share the list of articles I reference. Just looking through them gives a sense of the range of journals I was searching in. Archiv fur Hydrobiologie, The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, Entomol. Exp. Appl, American Statistician, Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci., Experimental Gerontology, The Auk, Annals: New York Academy of Sciences, Biol. Reprod, Maturitas, Administrative Science Quarterly, J. Herpetol., Ophelia, Genetica, Journal of the Institute of Actuaries and so on. I am lucky in that I didn't have to actually scan the tables of contents of the several thousand journals that could potentially have had relevant papers. I used Google Scholar, Web of Science and other literature searching tools. I have no idea how they did this sort of thing before the internet.

Like a good playbill, in order of appearance:

Main Article:

1. Medawar, P. B. 1952 An unsolved problem of biology. London: HK Lewis.

2. Metcalf, C. J. E. & Pavard, S. 2007 Why evolutionary biologists should be demographers. Trends Ecol. Evol. 22, 205-212.

3. Wachter, K. W. 2008 Biodemography comes of age. Demographic Research 19, 1501-1512.

4. Vaupel, J. W. 2010 Biodemography of human ageing. Nature 464, 536-542.

5. Moorad, J. A. & Promislow, D. E. L. 2009 What can genetic variation tell us about the evolution of senescence? Proc. R. Soc. Lond., Ser. B: Biol. Sci.

6. Péron, G., Gimenez, O., Charmantier, A., Gaillard, J. M. & Crochet, P. A. 2010 Age at the onset of senescence in birds and mammals is predicted by early-life performance. Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

7. Young, H. 1963 Age-specific mortality in the eggs and nestlings of blackbirds. The Auk 80, 145-155.

8. Deevey, E. S. 1947 Life tables for natural populations of animals. The Quarterly Review of Biology 22, 283-314.

9. Jones, O. R., Gaillard, J. M., Tuljapurkar, S., Alho, J. S., Armitage, K. B., Becker, P. H., Bize, P., Brommer, J., Charmantier, A. & Charpentier, M. 2008 Senescence rates are determined by ranking on the fast–slow life-history continuum. Ecol. Lett. 11, 664-673.

10. Pike, D. A., Pizzatto, L., Pike, B. A. & Shine, R. 2008 Estimating survival rates of uncatchable animals: The myth of high juvenile mortality in reptiles. Ecology 89, 607-611.

11. Carey, J. R., Liedo, P. & Vaupel, J. W. 1995 Mortality dynamics of density in the Mediterranean fruit fly. Experimental Gerontology 30, 605-629.

12. Pletcher, S. D., Macdonald, S. J., Marguerie, R., Certa, U., Stearns, S. C., Goldstein, D. B. & Partridge, L. 2002 Genome-wide transcript profiles in aging and calorically restricted Drosophila melanogaster. Curr. Biol. 12, 712-723.

13. Rose, M. R. 1984 Laboratory evolution of postponed senescence in Drosophila melanogaster. Evolution 38, 1004-1010.

14. Tatar, M., Carey, J. R. & Vaupel, J. W. 1993 Long-term cost of reproduction with and without accelerated senescence in Callosobruchus maculatus: analysis of age-specific mortality. Evolution 47, 1302-1312.

15. Bauer, G. 1983 Age structure, age specific mortality rates and population trend of the freshwater pearl mussel(Margaritifera margaritifera) in North Bavaria. Archiv fur Hydrobiologie 98, 523-532.

16. Styer, L. M., Carey, J. R., Wang, J. L. & Scott, T. W. 2007 Mosquitoes do senesce: departure from the paradigm of constant mortality. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 76, 111.

17. Sarup, P. & Loeschcke, V. 2010 Life extension and the position of the hormetic zone depends on sex and genetic background in Drosophila melanogaster. Biogerontology, 1-9.

18. Caughley, G. 1966 Mortality patterns in mammals. Ecology 47, 906-918.

19. Barlow, J. & Boveng, P. 1991 Modeling age-specific mortality for marine mammal populations. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 7, 50-65.

20. Spinage, C. A. 1972 African ungulate life tables. Ecology 53, 645-652.

21. Bruderl, J. & Schussler, R. 1990 Organizational mortality: The liabilities of newness and adolescence. Administrative Science Quarterly 35, 530-547.

22. Yang, G. 2007 Life cycle reliability engineering. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

23. Holliday, R. 2006 Aging is no longer an unsolved problem in biology. Annals: New York Academy of Sciences 1067, 1-9.

24. Hamilton, W. D. 1966 The moulding of senescence by natural selection. J. Theor. Biol. 12, 12-45.

25. Williams, G. C. 1957 Pleiotropy, Natural Selection, and the Evolution of Senescence. Evolution 11, 398-411.

26. Baudisch, A. 2008 Inevitable aging?: contributions to evolutionary-demographic theory: Springer Verlag.

27. Kirkwood, T. B. L. 1990 The disposable soma theory of aging. In Genetic effects on aging (ed. D. E. Harrison), pp. 9–19. Caldwell, NJ: Telford Press.

28. Holman, D. J. & Wood, J. W. 2001 Pregnancy loss and fecundability in women. In Reproductive ecology and human evolution (ed. P. T. Ellison), pp. 15–38. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter.

29. Woods, R. 2009 Death before Birth. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

30. O'Connor, K. A., Holman, D. J. & Wood, J. W. 1998 Declining fecundity and ovarian ageing in natural fertility populations. Maturitas 30, 127-136.

31. Kruger, D. J. & Nesse, R. M. 2004 Sexual selection and the Male:Female Mortality Ratio. Evolutionary Psychology 2, 66-85.

32. Bonduriansky, R. & Brassil, C. E. 2002 Senescence: rapid and costly ageing in wild male flies. Nature 420, 377.

33. McDonald, D. B., Fitzpatrick, J. W. & Woolfenden, G. E. 1996 Actuarial senescence and demographic heterogeneity in the Florida Scrub Jay. Ecology 77, 2373-2381.

34. Roach, D. A., Ridley, C. E. & Dudycha, J. L. 2009 Longitudinal analysis of Plantago: age-by-environment interactions reveal aging. Ecology 90, 1427.

35. Nussey, D. H., Coulson, T., Festa-Bianchet, M. & Gaillard, J. M. 2008 Measuring senescence in wild animal populations: towards a longitudinal approach. Funct. Ecol. 22, 393-406.

36. Sheader, M. 2009 The reproductive biology and ecology of Gammarus duebeni (Crustacea: Amphipoda) in southern England. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the UK 63, 517-540.

37. Milnes, M. R., Bryan, T. A., Katsu, Y., Kohno, S., Moore, B. C., Iguchi, T. & Guillette, L. J. 2008 Increased posthatching mortality and loss of sexually dimorphic gene expression in alligators (Alligator mississippiensis) from a contaminated environment. Biol. Reprod. 78, 932.

38. Anderson, D. J. 1990 Evolution of obligate siblicide in boobies. 1. A test of the insurance-egg hypothesis. Am. Nat. 135, 334-350.

39. Strandberg, R., Klaassen, R. H. G., Hake, M. & Alerstam, T. 2009 How hazardous is the Sahara Desert crossing for migratory birds? Indications from satellite tracking of raptors. Biol. Lett.

40. Moss, C. J. 2006 The demography of an African elephant (Loxodonta africana) population in Amboseli, Kenya. J. Zool. 255, 145-156.

41. Sumich, J. L. & Harvey, J. T. 1986 Juvenile mortality in gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus). J. Mammal. 67, 179-182.

42. Anderson, J. T. 1988 A review of size dependent survival during pre-recruit stages of fishes in relation to recruitment. Journal of Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Science 8, 55-66.

43. Gislason, H., Daan, N., Rice, J. C. & Pope, J. G. 2010 Size, growth, temperature and the natural mortality of marine fish. Fish Fish. 11, 149-158.

44. Baron, J. P., Le Galliard, J. F., Tully, T. & Ferrière, R. 2010 Cohort variation in offspring growth and survival: prenatal and postnatal factors in a late-maturing viviparous snake. J. Anim. Ecol. 79, 640-649.

45. Kushlan, J. A. & Jacobsen, T. 1990 Environmental variability and the reproductive success of Everglades alligators. J. Herpetol. 24, 176-184.

46. Congdon, J. D., Dunham, A. E. & Van Loben, R. C. 1993 Delayed sexual maturity and demographics of Blanding's turtles (Emydoidea blandingii): implications for conservation and management of long-lived organisms. Conserv. Biol. 7, 826-833.

47. Petranka, J. W. 1985 Does age-specific mortality decrease with age in amphibian larvae? Copeia 1985, 1080-1083.

48. Wilbur, H. M. 1980 Complex life cycles. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 11, 67-93.

49. Miller, T. J., Crowder, L. B., Rice, J. A. & Marschall, E. A. 1988 Larval size and recruitment mechanisms in fishes: toward a conceptual framework. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 45, 1657-1670.

50. Rabinovich, J. E., Nieves, E. L. & Chaves, L. F. 2010 Age-specific mortality analysis of the dry forest kissing bug, Rhodnius neglectus. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 135, 252-262.

51. Chapman, A. R. O. 1986 Age versus stage: An analysis of age-and size-specific mortality and reproduction in a population of Laminaria longicruris Pyl. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 97, 113-122.

52. Cole, K. M. & Sheath, R. G. 1990 Biology of the red algae: Cambridge Univ Pr.

53. Hett, J. M. 1971 A dynamic analysis of age in sugar maple seedlings. Ecology 52, 1071-1074.

54. Leak, W. B. 1975 Age distribution in virgin red spruce and northern hardwoods. Ecology 56, 1451-1454.

55. Harcombe, P. A. 1987 Tree life tables. Bioscience 37, 557-568.

56. Leverich, W. J. & Levin, D. A. 1979 Age-specific survivorship and reproduction in Phlox drummondii. Am. Nat. 113, 881-903.

57. Hanley, M. E., Fenner, M. & Edwards, P. J. 1995 The effect of seedling age on the likelihood of herbivory by the slug Deroceras reticulatum. Funct. Ecol. 9, 754-759.

58. Gosselin, L. A. & Qian, P. Y. 1997 Juvenile mortality in benthic marine invertebrates. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 146, 265-282.

59. Hallock, P. 1985 Why are larger foraminifera large? Paleobiology 11, 195-208.

60. Levin, L., Caswell, H., Bridges, T., DiBacco, C., Cabrera, D. & Plaia, G. 1996 Demographic responses of estuarine polychaetes to pollutants: life table response experiments. Ecol. Appl. 6, 1295-1313.

61. Greeff, J. M., Storhas, M. G. & Michiels, N. K. 1999 Reducing losses to offspring mortality by redistributing resources. Funct. Ecol., 786-792.

62. Klug, H. & Bonsall, M. B. 2007 When to care for, abandon, or eat your offspring: the evolution of parental care and filial cannibalism. The American Naturalist 170, 886.

63. Manica, A. 2002 Filial cannibalism in teleost fish. Biological Reviews 77, 261-277.

64. Lee, R. D. 2003 Rethinking the evolutionary theory of aging: Transfers, not births, shape senescence in social species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 9637-9642.

65. Rogers, A. R. 2003 Economics and the evolution of life histories. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 9114-9115.

66. Lee, R. 2008 Sociality, selection, and survival: Simulated evolution of mortality with intergenerational transfers and food sharing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 7124-7128.

67. Rumrill, S. S. 1990 Natural mortality of marine invertebrate larvae. Ophelia 32.

68. Jones, D. & Göth, A. 2008 Mound-builders. Collingwood VIC: CSIRO.

69. Chu, C. Y. C., Chien, H. K. & Lee, R. D. 2007 Explaining the optimality of U-shaped age-specific mortality. Theor. Popul. Biol. 73, 171-180.

70. Biro, P. A., Abrahams, M. V., Post, J. R. & Parkinson, E. A. 2006 Behavioural trade-offs between growth and mortality explain evolution of submaximal growth rates. Ecology 75, 1165-1171.

71. Sterck, F. J., Poorter, L. & Schieving, F. 2006 Leaf traits determine the growth-survival trade-off across rain forest tree species. Am. Nat. 167, 758-765.

72. Soler, J. J., de Neve, L., Pérez-Contreras, T., Soler, M. & Sorci, G. 2003 Trade-off between immunocompetence and growth in magpies: an experimental study. Proc. R. Soc. Lond., Ser. B: Biol. Sci. 270, 241-248.

73. Mangel, M. & Stamps, J. 2001 Trade-offs between growth and mortality and the maintenance of individual variation in growth. Evol. Ecol. Res. 3, 583-593.

74. Johnson, D. W. & Hixon, M. A. 2010 Ontogenetic and spatial variation in size-selective mortality of a marine fish. J. Evol. Biol. 23, 724-737.

75. Munch, S. B. & Mangel, M. 2006 Evaluation of mortality trajectories in evolutionary biodemography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 16604-16607.

76. von Bertalanffy, L. 1957 Quantitative laws in metabolism and growth. The Quarterly Review of Biology 32, 217-231.

77. Vaupel, J. W., Manton, K. G. & Stallard, E. 1979 The impact of heterogeneity in individual frailty on the dynamics of mortality. Demography 16, 439-454.

78. Vaupel, J. W. & Yashin, A. I. 1985 Heterogeneity's ruses: some surprising effects of selection on population dynamics. American Statistician 39, 176-185.

79. Charlesworth, B. 2001 Patterns of age-specific means and genetic variances of mortality rates predicted by the mutation-accumulation theory of ageing. J. Theor. Biol. 210, 47-65.

80. Mueller, L. D. & Rose, M. R. 1996 Evolutionary theory predicts late-life mortality plateaus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 15249-15253.

81. Moorad, J. A. & Promislow, D. E. L. 2008 A theory of age-dependent mutation and senescence. Genetics 179, 2061-2073.

82. Gong, Y., Thompson Jr, J. N. & Woodruff, R. C. 2006 Effect of deleterious mutations on life span in Drosophila melanogaster. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological and Medical Sciences 61, 1246-1252.

83. Pletcher, S. D., Houle, D. & Curtsinger, J. W. 1998 Age-specific properties of spontaneous mutations affecting mortality in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 148, 287-303.

84. Yampolsky, L. Y., Pearse, L. E. & Promislow, D. E. L. 2000 Age-specific effects of novel mutations in Drosophila melanogaster I. Mortality. Genetica 110, 11-29.

85. Wexler, N. S. 2004 Venezuelan kindreds reveal that genetic and environmental factors modulate Huntington's disease age of onset. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 3498-3503.

86. Wright, S. 1929 Fisher's theory of dominance. Am. Nat. 63, 274-279.

87. Orr, H. A. 1991 A test of Fisher's theory of dominance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88, 11413-11415.

88. Arbeitman, M. N., Furlong, E. E. M., Imam, F., Johnson, E., Null, B. H., Baker, B. S., Krasnow, M. A., Scott, M. P., Davis, R. W. & White, K. P. 2002 Gene expression during the life cycle of Drosophila melanogaster. Science 297, 2270.

89. Martinez, D. E. 1998 Mortality patterns suggest lack of senescence in hydra. Experimental Gerontology 33, 217-225.

90. Bakketeig, L. S., Seigel, D. G. & Sternthal, P. M. 1978 A fetal-infant life table based on single births in Norway, 1967-1973. Am. J. Epidemiol. 107, 216.

91. Human Life-Table Database. 2010 www.lifetable.de: Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Institut national d'études démographiques and UC Berkeley

Appendix 1.

1. Bourgeois-Pichat, J. 1946 De la mesure de la mortalité infantile. Population 1, 53-68.

2. Bourgeois-Pichat, J. 1951 La mesure de la mortalité infantile. II. Les causes de décès. Population 6, 459-480.

3. Wilmoth, J. R. 1997 In search of limits. In Between Zeus and the salmon: The biodemography of longevity (ed. K. W. Wachter), pp. 38-64. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

4. Carnes, B. A., Holden, L. R., Olshansky, S. J., Witten, M. T. & Siegel, J. S. 2006 Mortality partitions and their relevance to research on senescence. Biogerontology 7, 183-198.

5. Siler, W. 1979 A competing-risk model for animal mortality. Ecology 60, 750-757.

6. Gage, T. B. 1998 The comparative demography of primates: with some comments on the evolution of life histories. Annual Review of Anthropology 27, 197-221.

7. Heligman, L. & Pollard, J. H. 1980 The age pattern of mortality. Journal of the Institute of Actuaries 107, 49–80.

8. Lee, E. T. & Go, O. T. 1997 Survival analysis in public health research. Annu. Rev. Public Health 18, 105-134.

9. Ndirangu, J., Newell, M. L., Tanser, F., Herbst, A. J. & Bland, R. 2010 Decline in early life mortality in a high HIV prevalence rural area of South Africa: evidence of HIV prevention or treatment impact? AIDS 24, 593.

Appendix 2

1. Bishop, M. W. H. 1964 Paternal contribution to embryonic death. Reproduction 7, 383-396.

2. Wilcox, A. J., Weinberg, C. R., O'Connor, J. F., Baird, D. D., Schlatterer, J. P., Canfield, R. E., Armstrong, E. G. & Nisula, B. C. 1989 Incidence of early loss of pregnancy. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey 44, 147.

3. Boklage, C. E. 1990 Survival probability of human conceptions from fertilization to term. International Journal of Fertility 35, 75-94.

4. O'Connor, K. A., Holman, D. J. & Wood, J. W. 1998 Declining fecundity and ovarian ageing in natural fertility populations. Maturitas 30, 127-136.

5. Hassold, T. & Hunt, P. 2001 To err (meiotically) is human: the genesis of human aneuploidy. Nature Reviews Genetics 2, 280-291.

6. Beatty, R. A. 2008 The genetics of the mammalian gamete. Biological Reviews 45, 73-117.

7. Wilmut, I., Sales, D. I. & Ashworth, C. J. 1986 Maternal and embryonic factors associated with prenatal loss in mammals. Reproduction 76, 851-864.

8. Bloom, S. E. 1972 Chromosome abnormalities in chicken (Gallus domesticus) embryos: types, frequencies and phenotypic effects. Chromosoma 37, 309-326.

9. Forstmeier, W. & Ellegren, H. 2010 Trisomy and triploidy are sources of embryo mortality in the zebra finch. Proc. R. Soc. Lond., Ser. B: Biol. Sci.

Monday, November 08, 2010

A botanist once told me...

Botanists have to make up dirty rhymes because they can't just take fecal samples the way zoologists do.

Monday, November 01, 2010

Halloween, diversity, and the left-leaning scientists

One could easily suggest several possible reasons for left-lean. The liberal might say that scientists are people trained to think carefully about ideas, and liberal ideas stand up to careful thought better than their conservative counterparts. She could add that conservatives, particularly the United States, tend to engage in a great deal of anti-intellectualism, which is not a good way to win the support of scientists and that conservative leaders and movements twist scientific conclusions and ideas more frequently and more disastrously than do liberals. A conservative could argue that as a big-spending liberals tend to support science funding, scientists have a direct interest in supporting liberals. I think all of these things are at least sometimes true.

Another hypothesis occurred to me last night during our Halloween party. Looking around our apartment, I saw not only several Americans (tiger, mime, fisherman, pirate, little girl/trick-or-treater, scarecrow, frog, Dorothy, lumberjack, but no tricorn hats) and Germans (lizard, clown, flapper, schoolgirl, bus stop, Little-Red-Riding-Hood, ninja, and a little boy dressed as a little boy), but also friends from Italy (a mouse and a mummy), Hungary (bank robber), Austria (ghost and witch), Australia (tin man and geisha), Poland (burglar, witches and a ghost), Latvia (witch), Spain (ghost and sorceress) and Finland (clown, penguin, bear and ladybug). We had 34 people from 10 countries, and had invited people from at least a dozen more (Japan, Taiwan, China, Mexico, Brazil, the Netherlands, Denmark, England, Russia, Bulgaria, Turkey and New Zealand). This sort of national diversity is common at gatherings of Institute researchers. I had a similar experience at Berkeley, with colleagues from all over the world.

Conservatives in many countries are nationalistic, or at least view the traditional ways of doing things in their part of the world as best and most correct. So perhaps the conservative hoping to build a career in science finds herself in many uncomfortably international situations, where her assumptions are challenged or potententally unpopular. If so, such people may tend to either revise their opinions (or pretend to, which often eventually leads to an actual change) or avoid such situations. Such avoidance would make a successful career in science difficult, at least at the prestigious institutions which tend to have international research staff.

The Ivory Tower's relative lack of political diversity may partly result from its high demographic diversity. It is hard to condemn witches when your living room is full of them.

Monday, October 18, 2010

Cold Season

it hovered in a frozen sky, and gobbled summer down."

-Joni Mitchell

Rostock has its first real frost this morning. In anticipation of this event, the first bad cold of the year has been going around. I think about half the Institute has gotten it so far. I have been sick to varying degrees for a week now. Without having actually looked at the relevant research, my understanding is that we get so many more colds when it gets colder because the airborne viruses break down much more slowly when the areas cold and dry and sunlight is weak. I've also heard somewhere that the cold air makes mucous membranes more susceptible to viruses. This all makes sense, and helps explain why that other common airborne virus that spreads every year, the flu, also concentrates in winter, but it leaves me wondering this: is the pattern the same in species that are adapted to highly seasonal climates? Humans are basically a tropical species that construct tropic-like microclimates for ourselves wherever we go. Our ancestors a few thousand generations ago would not have experienced the yearly cold season as we do today. Moose on the other hand have been living in cold climates forever. Their bodies should expect high virus conditions every winter and prepare accordingly. I speculate that the immune systems of such animals are seasonal, being better at fighting airborne viruses in the winter, and perhaps skin fungus is in the summer. I wouldn't personally want to do the experiments to find out, but I would read the paper if somebody else wrote it.

Saturday, October 16, 2010

Not buying a PC

Friday, October 15, 2010

The LPU

The Least Publishable Unit has a long and proud history in science. It is often the case that one can either toil for months over a very long paper, or chop that up into several smaller papers which will come out faster, often in lower profile journals. The quality of the work is not necessarily any lower, but the step is more incremental and the CV filled out faster. This particular LPU is a simple reanalysis of some data from my doctoral work. I started writing it today, and expects to have completed draft by sometime next week. I will submitted to a low-profile journal with rapid turnaround and hope to have an answer from them before I send in my CV.

I do not feel at all bad about this, my first LPU, for several reasons. First, looking through the CVs of most of the very successful scientists I know, there are quite a few little papers among their giant publications. Second, I can think of several papers which seem to me to have started out as LPUs but which turned out to be tremendously important and widely cited. Third, experience and mentors have told me people are more likely to read a short paper. Fourth and finally, writing short papers is a hell of a lot easier when one has to dictate everything.

There is one way in which this paper does not really meet the classical definition of an LPU: there are lots of data behind it. The true LPU should have just enough data to make a publishable paper. In this case, the sample being analyzed is fairly enormous, although not much bigger than is needed to answer the question.

All in all, writing a little paper seems a good change from the massive review article I've just submitted. I hope it turns out to be as easy as I think it will.

Friday, October 08, 2010

Big grant, small grant application

Assuming I can convince them of these things, more so than the many other applicants, it will be a pretty sweet deal. They will not only give me a significantly increased salary for five years and enough funding to get my experiments going, they will pay for me to hire a couple of graduate students and a postdoc or two. Frankly, this is more of a career advance than I think I am likely to receive at this point.

The nice part, other than the generosity of the award should I get it, is how little work they ask of me for the application. They want only a one-page statement of my Scientific Accomplishments (I'm not sure what these are yet) plus 2 pages of Research Plans. I could give them 20 pages of research plans with little difficulty if my hands worked well, but under the circumstances I'm much happier to give them 2.

How my health issues will work into this whole application is an interesting question. There is no doubt that I would have been more productive this year and in grad school had been healthy, but I doubt that they can or should take this into consideration. The best I can hope for is that one of my letter writers will mention something about dedication to science or gumption or the fact that I just keep coming back, like a bad case of poison ivy.

On a more philosophical level, I can ask this question: if someone has a disability which interferes with their productivity, and is likely to continue interfering with their productivity, should an employer consider how productive the worker would be without the disability, or should they simply asked of each candidate, "how productive is he/she likely to be?" I would like to say the former, but from the employer's point of view, it's hard to make the case against the latter.

On the other hand, my joint problems potentially make me better qualified to think of the questions and tell other people to gather the necessary data to answer them than I am for actual data gathering and analysis. The higher they promote me, the more qualified I may be.

Friday, October 01, 2010

The news from me

I had carpal tunnel surgery on my left hand about a month ago and am pleased to report that had very little numbness or tingling since then in that hand. I still have pain around where the incision was and some of the internal cuts but they assure me that will fade with time. I'm having the same surgery on my right hand on Monday. I'm supposed to be on sick leave for all of next week, but I suspect I'll end up coming in to use the dictation software, as I don't have it at home (I have a Mac it works on PC.) I hope that by the end of the year I'll be able to use my hands fairly normally again.

I also just found out today that a large grant application I need to submit is due on November 17. This may interfere somewhat with my plans to post here more regularly.